Thomas McDade, a organic anthropologist at Northwestern College, nonetheless remembers an commercial for chilly drugs he noticed in late 2019. The advert confirmed a visibly sick businessman strolling by an airport, “and the message was, ‘You’ll be able to solider by this. You can also make it,’” McDade says.

That message didn’t age effectively. Just a few months later, the virus that causes COVID-19 started spreading throughout the globe, prompting well being officers to beg folks to remain residence it doesn’t matter what—however particularly in the event that they felt sick. Instantly, soldiering by an sickness wasn’t seen as admirable, however irresponsible, egocentric, and harmful.

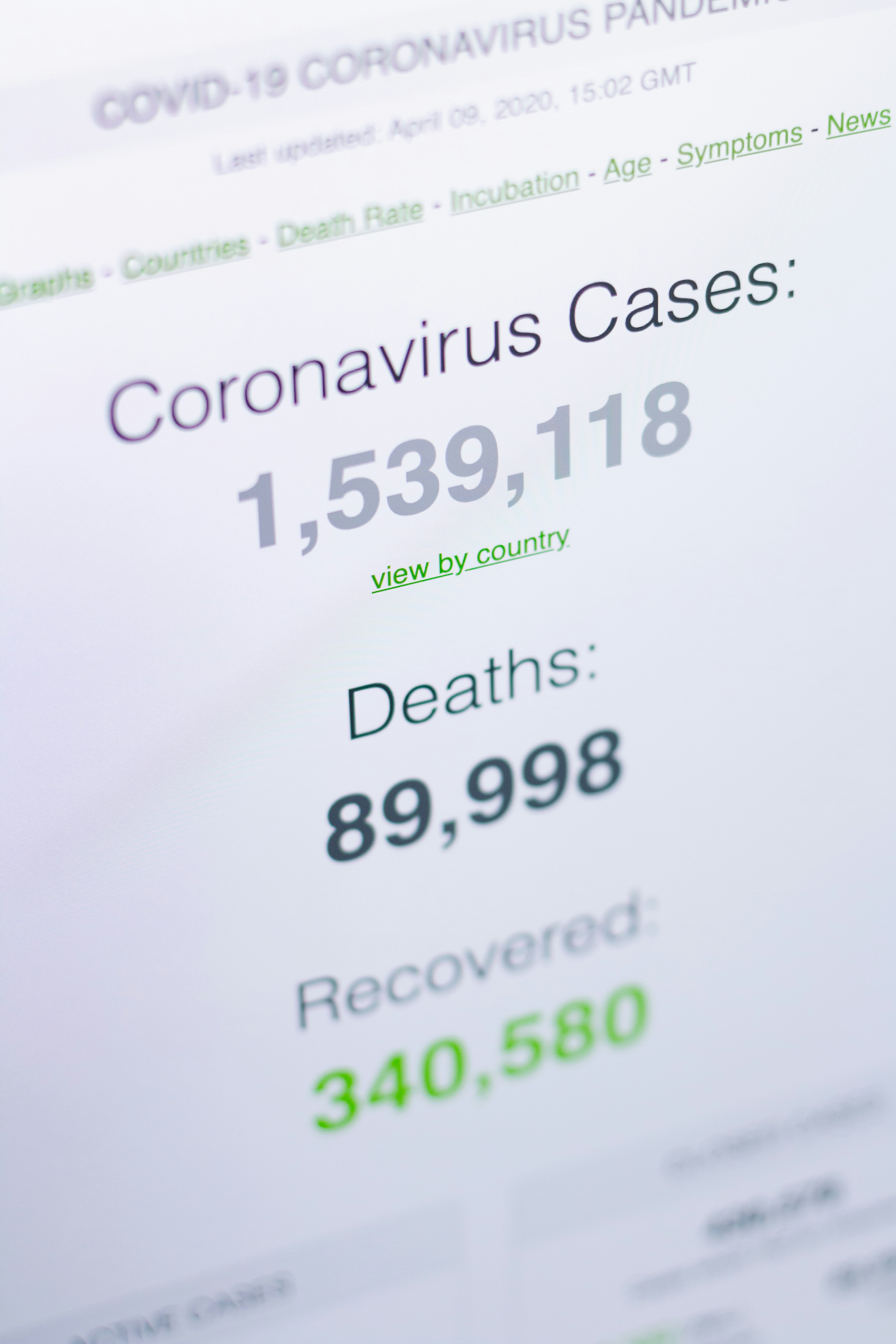

Since then, numerous op-eds and articles have argued that the pandemic would usher in a “new regular” the place folks had been extra considerate about illness, firms had been extra beneficiant with sick time, and everybody stayed residence when unwell. It appeared prefer it was occurring, a minimum of for some time. Tens of millions of individuals labored and discovered from residence, many for the primary time; evaluating signs turned a nationwide pastime; and photographs of at-home take a look at strips crowded out trip photographs on social media.

However now, with the pandemic successfully over—a minimum of when it comes to the federal response, if not epidemiologically—plainly the promised new regular by no means absolutely materialized.

Eric Shattuck, an assistant professor of analysis on the College of Texas at San Antonio, research “illness conduct:” the constellation of behavioral adjustments that individuals undertake once they’re sick, like lethargy, social withdrawal, and decreased urge for food. A lot of illness conduct is organic, pushed largely by irritation within the physique. However the extent to which individuals carry out these behaviors is knowledgeable by cultural norms about how we’re “supposed” to behave when sick, Shattuck says.

Although pushes to remain residence and “flatten the curve” modified conduct early within the pandemic, they weren’t sufficient to enduringly alter dominant cultural messages about sucking it up and soldiering by, Shattuck says—largely as a result of they weren’t backed up by supportive coverage adjustments, like expanded entry to paid sick depart and reasonably priced baby care.

“We might even see that persons are paying extra consideration and listening to their our bodies extra,” Shattuck says, “but when the situations aren’t there for them to have the ability to keep residence or make money working from home…it could not really change the large-scale behaviors.”

The beginning of the pandemic introduced a flurry of latest sick- and family-leave insurance policies, however many had been short-term or didn’t apply equally to all staff. As of March 2022, 77% of private-industry staff had entry to paid sick time, solely barely greater than the 75% who did in March 2020, in response to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). However that top-line statistic doesn’t inform the entire story.

Learn Extra: As Individuals Return to Workplaces, It’s Again to Distress for America’s Working Mothers

Whereas 96% of individuals working within the administration, enterprise, and monetary sectors had entry to paid sick time in 2022 (together with the choice to work remotely in lots of circumstances), solely 62% of service-industry staff did—up barely from 59% in 2020. Solely about 40% of the lowest-paid private-industry staff had paid sick time in 2022, versus almost all the highest earners, BLS knowledge present.

Total, through the first two years of the pandemic, solely 42% of labor absences associated to sickness, baby care, or private obligations had been compensated, in response to a report from the City Institute, an financial and coverage analysis institute. Many staff, particularly these least in a position to afford it, nonetheless have to decide on between getting effectively and getting paid. It’s laborious to fault folks for selecting the latter.

Even individuals who have paid sick time usually work by their diseases, and that didn’t change through the pandemic. In some respects, says Kai Ruggeri, an assistant professor on the Columbia Mailman College of Public Well being who research inhabitants conduct, the rise of distant work really made it tougher for folks to justify taking sick time. A number of folks appeared to suppose, “‘What’s the distinction, should you get some issues achieved out of your laptop computer in mattress?’” Ruggeri says.

In 2020, researchers surveyed folks with COVID-like signs about whether or not they labored whereas sick. (A couple of quarter of them ended up testing constructive for COVID-19, whereas the remaining had different respiratory diseases.) About 42% of individuals with COVID-19 labored both remotely or in-person whereas sick, and 63% of individuals sick with one other respiratory sickness did so. One 2023 examine even discovered that, inside a gaggle of about 250 well being care staff with symptomatic COVID-19, half labored a minimum of a part of a day anyway.

That could be as a result of many staff nonetheless really feel strain—spoken or unstated—from their employers to point out up irrespective of their well being standing, says Terri Rhodes, CEO of the Incapacity Administration Employer Coalition, which offers employers with steerage on office absences. The pandemic didn’t change that. “The overall feeling that I get from employers is, ‘We simply need to be achieved with [the pandemic],’” Rhodes says. “There’s an enormous push proper now for productiveness and earnings and ‘simply get again to work,’ versus psychological well being, well-being, taking sick days.”

The previous regular—the one valuing stoicism, productiveness, not stopping for a second—has confirmed laborious to uproot. However there have been adjustments round the way in which we take into consideration sickness: the truth that persons are even speaking about sick-leave insurance policies and forming opinions in regards to the deserves of vaccinations and masks (for higher or for worse) suggests there’s been a tradition shift round well being and illness, Ruggeri says.

As director of the Annenberg Public Coverage Heart of the College of Pennsylvania, Kathleen Corridor Jamieson oversees analysis initiatives that assess how a lot the U.S. inhabitants is aware of about well being and science. Over the course of the pandemic, Jamieson says, she’s seen two contradictory issues occur in parallel: total scientific literacy grew, whilst extra folks started to imagine conspiracy theories and misinformation.

The truth that many of the U.S. inhabitants acquired vaccinated and wore masks on the peak of the pandemic suggests most individuals usually understood how the virus spreads and tips on how to gradual transmission, Jamieson says. In a survey fielded across the time COVID-19 vaccines turned out there to most people, round three-quarters of respondents accurately answered questions in regards to the security and efficacy of the photographs. Outcomes like these present “an astonishing stage of public literacy a few matter that we knew nothing about in January 2020,” Jamieson says.

Learn Extra: This Emergency Is Over. Now It’s Time to Get Prepared for the Subsequent Pandemic

Ideas as soon as international to many of the common public—like incubation intervals and airborne transmission—additionally turned a part of common dialog. “No person knew what an R worth was” earlier than, Ruggeri says. “I had folks calling me, asking me to clarify it to them.”

For many individuals, the pandemic was a primary introduction to a “blind spot” within the medical world, as a 2022 analysis evaluate put it: post-acute sickness. Viruses starting from influenza to Epstein-Barr may cause probably debilitating long-term issues, however that actuality went largely unnoticed till scores of individuals developed Lengthy COVID signs—starting from mind fog and reminiscence loss to continual fatigue and ache—inside roughly the identical time frame. For some folks in each the medical area and most people, these long-term signs reframed what a seemingly “delicate” sickness might do.

Along with elevated scientific literacy, Dr. Yuka Manabe, a professor at Johns Hopkins Medication who focuses on infectious illness, has seen a stronger need for “diagnostic certainty” amongst sufferers. In 2019, somebody with a respiratory sickness may need been content material to say they had been sick and depart it at that, however many sufferers now need to know precisely what they’ve and the place they caught it. “I hear lots of people say, ‘I’ve a chilly, however don’t fear as a result of it’s not COVID—I examined myself,’” Manabe says.

The unprecedented availability of at-home exams doubtless contributed to that need for certainty—and shopper demand for COVID-19 diagnostics appears to have carried over to different situations, too. In a 2022 survey, 82% of adults ages 50 to 80 mentioned they had been a minimum of considerably inquisitive about utilizing at-home exams sooner or later. They usually might certainly get the possibility. In February 2023, the U.S. Meals and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the primary mixed at-home influenza and COVID-19 take a look at.

However whereas COVID-19 turned some folks into novice illness detectives, many others—about 40% of U.S. adults, in response to federal knowledge—delayed or prevented well being care through the pandemic. One 2022 examine discovered that lower-income folks and people with preexisting situations had been more likely to delay care in 2021, which means that monetary stress and concern of the virus performed a job. One other examine from 2022 discovered that individuals had been extra more likely to skip docs’ visits through the pandemic in the event that they’d beforehand had dangerous experiences with medical care.

It is smart that individuals who’d had earlier dangerous experiences—a gaggle that tends to incorporate folks of coloration, lower-income folks, these with out insurance coverage—might have shied away from the medical institution through the disaster, whilst others actually trusted it with their lives. Throw in partisan polarization, which made even fundamental practices like masking and vaccination really feel like political statements, and it’s no surprise that individuals responded very in a different way to the identical well being menace. How might there be a single new regular when the previous regular diversified a lot by race, class, gender, and age?

Regardless of the divisions, nonetheless, Jamieson says she’s optimistic that a minimum of a number of the data gained through the pandemic will stick round, able to be deployed if and when there’s the same menace sooner or later. For many individuals, behaviors like masking and handwashing turned routine through the pandemic, and “you don’t unlearn routine behaviors,” Jamieson says.

Though far fewer folks put on masks now than on the peak of the pandemic, Manabe says she’s seen that individuals at the moment are faster to put on one once they have respiratory signs—an indication, she thinks, that individuals perceive how pathogens unfold and need to shield others.

“This sort of social altruism is basically welcome, from my viewpoint,” Manabe says. “We’re attempting to maneuver ahead as a society within the post-COVID period.”

Extra Should-Reads From TIME